Bacterial resistance

Outline the mechanisms of bacterial antibiotic resistance

Drug modification

Bacteria produce an enzyme that inactivates the antibiotic.

Examples:

- Some bacteria, including some Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, produce beta-lactamases or extended-spectrum beta lactamases (ESBL) which hydrolyse the beta-lactam ring on beta-lactams antibiotics, inactivating them (enzyme inactivation).

- Common resistance patterns to aminoglycosides in Staphylococcus aureus are via the addition of functional groups to the antibiotic (e.g. acetylation), inhibiting its action (enzyme addition).

Preventing access to the drug target

Impermeability

Bacteria decrease the permeability of their cell membrane to an antibiotic.

Examples:

- Beta-lactams gain entry to gram negative cells by diffusing through porin channels in the cell membrane. Mutations in porin genes decrease permeability to beta-lactams.

- Aminoglycosides diffuse through the bacterial cell membrane by oxygen-dependent active transport. Anaerobes lack these transport channels which prevents their penetration.

Antibiotic efflux

A bacteria ejects the antibiotic via an efflux pump.

Example:

- Doxycycline resistance in E. coli is due to the synthesis of cytoplasmic membrane proteins that pump the tetracyclines out of the cell.

Modification of cell processes

Alteration of the drug target

Bacteria alter the target site, decreasing or preventing the antibiotic's affinity for it. Many common and important resistance patterns occur by this method.

Examples:

- MRSA produces an alternative penicillin-binding-protein known as PBP2a, encoded by the mecA gene, which has a lower affinity for beta-lactams.

- VRE alters its peptidoglycan wall precursors from D-Ala-D-Ala to D-Ala-D-Lac by acquisition of the vanA gene, preventing the binding of vancomycin.

- E. coli resistance to trimethoprim is via alteration of the genes that synthesise dihydrofolate reductase, which prevents the binding of trimethoprim.

Alteration of a metabolic pathway

Bacteria alter their metabolic processes so that the antibiotic is ineffective.

Examples:

- Sulfamethoxazole resistance in Staphylococcus aureus is due to an increased production of para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), which is used to synthesise folic acid via the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase. Sulfamethoxazole is a competitive antagonist of dihydropteroate synthase which is outcompeted by the increased concentration of PABA, allowing folic acid synthesis to continue.

- Some bacteria have evolved mechanisms such that they do not require PABA for folic acid synthesis at all, which also confers resistance to sulfamethoxazole.

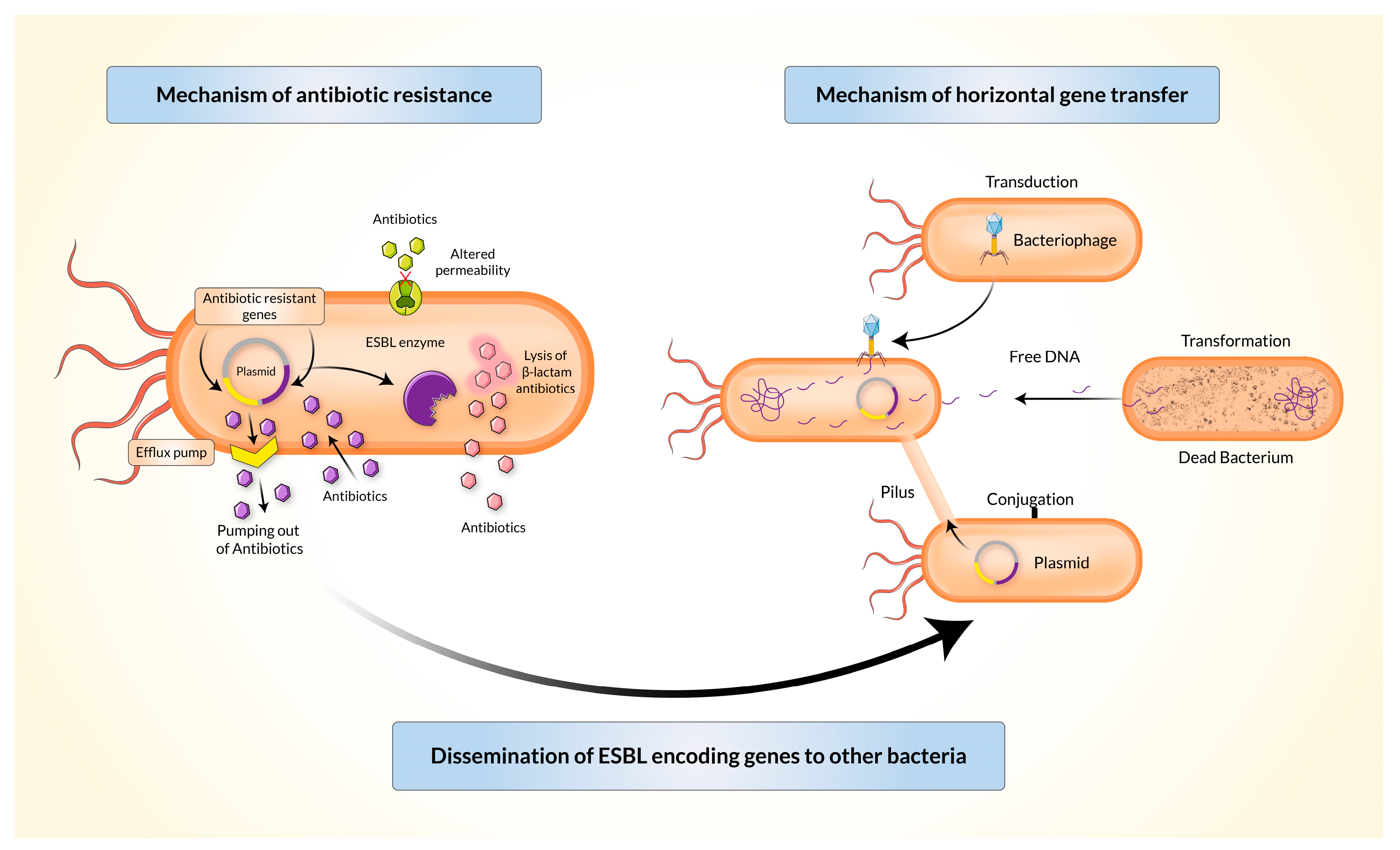

By Husna et al. CC-BY published in Biomedicines

How is bacterial resistance is spread?

Spontaneous gene mutation

A spontaneous gene mutation may alter protein synthesis, interfering with the action of an antimicrobial in one of the following ways:

- destruction of an antibiotic

- efflux of the antibiotic out of the bacterium

- preventing the antibiotic from diffusing into the cell (non-permeability)

- alteration of the antibiotic target, preventing it from binding or acting

- changing a metabolic function of the bacterium, such that it interferes with the mechanism of action of the antibiotic

Host-host spread

A host who is infected or colonised by a resistant organism may transfer these organisms to a new host, for example by respiratory droplets.

Horizontal gene transfer

All mechanisms of resistance are encoded in a bacterium's DNA. This DNA can be transferred between bacteria, conferring resistance, a process known as horizontal gene transfer.

Horizontal gene transfer occurs via one of three ways:

- Transduction

- a bacteriophage (virus) infects a resistant bacteria and replicates within it, internalising some bacterial DNA fragments during this process

- the bacteriophage then infects other bacteria, carrying DNA fragments with it which are incorporated into the new bacteria's genome

- Transformation

- a resistant organism lyses and its DNA is released and taken up by nearby bacteria

- Conjugation

- plasmids are loops of double-stranded DNA which are independent of the bacterial nucleoid

- they acquire resistant genes which can be transferred to a neighbouring bacteria by cell-cell contact and the formation of a bridge between the bacteria